Meanwhile, there was suddenly my father to take care of. Now in his early eighties, his heart was beginning to falter.

A hard-charging, ideas-oriented, problem-solving, adventure-loving workaholic, he’d been through open-heart surgery and seven bypasses – a number he was weirdly competitive about – brought on by two massive heart attacks during the years he’d lived and worked in southern California.

He moved east after the second one, settling just outside of Philadelphia in a strategically optimal location. Nearby was his easy-going younger brother, Frank, with his charming and cheerful Ethiopian wife, Stella, and their grown daughters and grandchildren. His brother Larry, the retired New York Times foreign correspondent, lived three hours to the north with his German wife, Ruth. The kids and I lived three hours to the south.

Together we rotated our visits to his townhouse, celebrating everything possible. Dad was always a convivial and happy host. Nothing was ever a problem. He delighted in each visitor and never minded how late the parties ran – and they tended to run well into the night when any of our Ethiopian family was involved.

By 2003, however, my father’s health began to deteriorate. My long-distance visits increased to once, then twice a month – three to five hour drives up and down I-95 in the midst of what often seemed to be a dense and slow-moving scrum of traffic.

And then one day I got a call from my Ethiopian cousin, Gladys, the one person who helped Dad the most. My father was in the hospital yet again, she told me. The challenges of living independently in a multi-level townhouse had become too difficult. The time had come for me to consider a different living arrangement. I sighed and started packing my overnight bag yet again. I’d only been back home for six days. Fortunately, the kids were now thirteen and sixteen – old enough to manage by themselves, especially with their dad living nearby.

On my way out the door, I remembered a film I’d recently seen at the Goethe Institute downtown – The Price of Freedom: The Untold Story of America’s WWII Prisoners of War. The documentary featured a group of veterans who discovered one other in the later years of their lives. They met weekly to talk and help one another deal with their painful memories of being a POW. Directed by award-winning National Geographic filmmaker, Bruce Norfleet, it was a semi-finalist in the Short Documentary category at the 2002 Academy Awards.

After the screening, I’d reached out to Bruce to ask if he might be interested in having me promote it to PBS stations around the country. I knew it would do well with a public television audience. He sent me a DVD and we agreed to a small outreach plan.

Dad had not been a POW himself, but he’d served in the Army during WWII. He once told me he was classified as D6 – a soldier who arrived at Normandy on the 6th day of the invasion, he explained. Thinking he might be interested in seeing the film, I grabbed the DVD from my desk and stashed it in my backpack. I always liked to bring him little surprises and I also wanted to hear more about his own experiences in France and Germany during the war. Perhaps watching the film together would trigger some stories I hadn’t yet heard.

Happy I was en route to help Dad, despite everything going on in my life, I was in good spirits until I reached the hospital. It was a maze of confusion. And when I finally located Dad, his appearance startled me. It had only been six days since I’d last seen him but now his skin seemed to hang off his arms, his face was haggard, and his legs had mysteriously ballooned. Dark red and purple blotches covered his hands and forearms, reminding me of one of the kids’ preschool paintings.

My sense of humor, inherited from my dad and always my surest and most ready companion, fled the scene, leaving me alone and unprepared, unsure of myself and uncertain of what to do.

“Your software is great, Dad, but your hardware’s letting you down,” I finally said softly, hoping the analogy might soften the news. My father was not just an old soldier – he’d also been a pioneer in the world of computers.

After serving in the Army during World War II, Dad got a job working on the ticket counter for Eastern Airlines at Washington DC’s National Airport. Always an ideas kind of guy, from that simple beginning, he rose to General Manager for Data Processing. And after that, he was promoted to Eastern’s VP of customer service where, in the early 1960s, he set up the first real-time computerized reservations center for the airline industry. The daily shuttle service between Washington DC and New York City was his idea, as well as the concept of curbside check-in. He loved having new ideas and solving problems and was in his element when doing a combination of both. I’ve inherited that from him, too.

In 1964, Dad changed jobs again, becoming the London-based project manager for Univac’s largest overseas client, British European Airways or BEA. I was just eight years old when we moved to England.

Dad knew about the power of computers from his awareness of how NASA used them to process information that kept guided missiles on course.

“How many little bits of information do you suppose are floating around this company?” he once mused to a reporter. “Millions? And how many managers need bits of the same information at the same time?”

Once the NASA information was declassified, he began applying it to the airline industry. From there, his career in the nascent field of computers took him from one interesting job to the next, from London to New York, then back to London, Chicago and eventually California.

He retired in the mid-1990s and moved to Philadelphia.

After the hospital released him, I took Dad grocery shopping, then back home to his townhouse. Over dinner, my resolve strengthened by a glass of red wine, I gingerly broached the conversation about moving to some type of retirement home – a conversation I’d been dreading, fraught as it could be with hurt feelings, depression, restrictions, and loss of independence, especially for someone like my dad.

To my surprise, Dad was fine about discussing it. He even seemed to welcome it. But his end of the conversation consisted mostly of telling me where he didn’t want to go. At least it was a start, I thought, and left it at that.

We turned our attention to dessert. He was delighted with the homemade pumpkin pie I’d brought from my mother and launched into a story of how he’d managed to keep two pies to himself on a crowded troop train during WWII by giving away all his sandwiches to the guys around him and keeping the pies.

Although his appetite had been skimpy, he ate two pieces of pie that night. Remembering the DVD, I retrieved it from my backpack, told him what it was about and asked if he’d like to see it.

“Sure!” he said, settling back in his rocking chair, wine by his side, always amenable to my film and television suggestions.

We sat side by side, watching wordlessly in his darkened living room. Then, as the closing credits ran, a thought occurred to me.

“Hey, Dad, that’s what you need!” I said. “A collection of buddies who have the same shared experience!”

He nodded in agreement. But where to find them? His own friends from WWII days, if they were even still alive, were dispersed all over the world. I refilled our wineglasses as we pondered the idea. Suddenly, his eyes widened, and his dark eyebrows shot up.

“Hey, what’s that place in DC?” he said. “That place for old soldiers?”

“The Old Soldiers Home?” I said.

“That’s it!” he said happily. “Is that still there?”

“It is!” I said, smiling back at him.

And how did I know about it? There was, of course, another documentary film tie-in.

The Old Soldiers' Home, located high on a leafy and beautiful 350-acre expanse with views of Washington DC was founded in 1851. From the top floors of the residence buildings, it’s possible to see the Washington Monument, the Potomac River and the dome of the Capitol.

According to Washington Post writer, Steve Vogel, “Congress used booty from the Mexican War to establish an ‘asylum for old and disabled veterans.’

“The elderly soldiers and airmen now at the home, most of them veterans of World War II or the Korean War, live in hotel-size dormitories amid a miniature city unknown to most area residents, complete with its own chapels, gymnasium, golf course, library and fishing lakes.”

Dad didn’t play golf, but other than that, he agreed, it was a perfect solution for him.

Back when we were in production on American Byzantine, Martin had thought it would be a good idea to shoot some aerial footage given the Basilica’s unusual architecture. While we were preparing to do this, we received a request to capture aerial shots of the land the Old Soldier’s Home had been forced to sell to the archdiocese – and that was my introduction to the facility with its storied history.

The following day, I began researching how to get Dad into the Armed Forces Retirement Home. It was a community of 1200 soldiers from all over the country, both male and female, all of whom had seen active duty, from WWII, Korea, Vietnam, and Operation Desert Storm. Dad’s Normandy service qualified him.

I booked a tour for the two of us, then drove back up to Philadelphia to pick up Dad and bring him back down to DC to see it. Driving through the gates felt like driving onto the grounds of a beautiful and well-established old university.

Abraham Lincoln used what is now the Old Soldiers’ Home as his ‘Summer White House.’ Each spring, before it got too hot, his staff would load up the White House furniture in a horse drawn cart, retreating for each of the summers during the Civil War to escape the heat and humidity of the city. Lincoln wrote the last draft of the Emancipation Proclamation in a Gothic Revival-style cottage on the campus. Now called the Lincoln Cottage, it’s a designated National Monument.

Each fall, the president’s furniture would be loaded on the cart and moved back down to the official White House.

In addition to the 9-hole golf course, there was a state-of-the-art bowling alley, a 700-seat movie theater, a 40,000-book library, computers to use everywhere, a room full of jigsaw puzzles and vending machines that sold beer as well as soda. Dad loved that. They even had studios for artists and woodworkers along with five or six kilns for pottery. Pondering the unlikelihood of an old soldier’s home having pottery kilns felt like getting a surprise thumbs up from Karen, as if she was there with us and putting her personal stamp of approval on this phase of Dad’s transition. I could almost hear her laughing at our surprise.

Over the next few months, as I dealt with the paperwork to get him in, Dad rose to the occasion and was a good sport about all the changes. He gave away most of his treasures to relatives, pleased they were staying in the family. Everyone wanted something to remember him by. We sold his house to one of my Ethiopian cousins, saving us all from the cold thought of strangers living there where so many family gatherings had taken place.

In case he tried to change his mind, I did my best to scare him with a number of unsavory options. But I needn’t have bothered. Dad loved the idea of joining his own ‘band of brothers,’ and of going ‘back into the Army,’ as he told everyone with a grin.

Adding to that, Dad was happy to be back in his hometown, Washington DC – the town where he went to high school, where he coached local teams, and his parents lived for years. The town where he went to American University, where he met and married my mother, and where his first two children were born. He loved the idea of his life coming full circle. It felt right.

Best of all, though, the Old Soldiers’ Home was filled with hundreds of potential buddies for Dad – guys he had stories in common with. The day I moved him in, I hung his WWII uniform on the door to his room as a conversation starter, to let people know who he was. Dad was delighted with the greetings, welcomes and conversations it attracted from the old soldiers walking past en route to their own rooms. Friendships were born.

Located in the northeast part of the city, the Old Soldiers’ Home was just an hour away from my own home in south Alexandria. I visited Dad every week, often with the kids, sometimes taking him out somewhere, but usually just hanging out with him for a meal, sometimes joined by one or two of his new buddies. Although there was a nice dining room, which Dad called a ‘mess hall’ – his favorite place, not surprisingly, was the pub with its cozy atmosphere, friendly servers, grilled cheeses, and martinis. We’d hole up there for hours – him talking, asking a few questions about the kids and my work, and me listening to his stories.

That summer, my cousin Gladys had the inspired idea to throw a family reunion for him on the grounds of the Old Soldiers’ Home. Dozens of relatives came, including all of our Ethiopian family.

It was a wonderful celebration – and the last time most of them would see him.

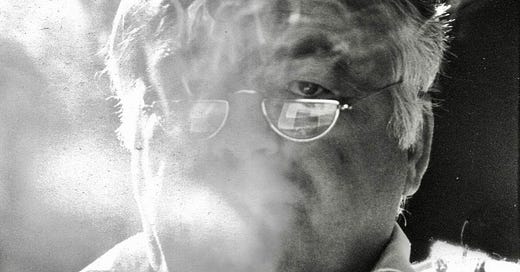

[photograph of Dad by Robin Fellows]

Kristin Fellows is a published writer, world traveler, and a well-seasoned documentary film consultant. When not writing, Kristin can often be found listening to someone’s story or behind the lens of one of her cameras.

More about Kristin @ kristinfellowswriter.com

The WW2 combat vets I knew were not healthy. The byproducts of warfare are toxic, the chemicals left behind from explosives, the poor food, free cigs, etc. Not to mention the stress of seeing all that carnage. God bless your father and our vets. It was a lifetime of service.

He is. We are in touch occasionally. When there's something to say...